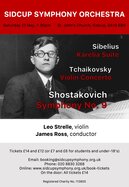

SIDCUP SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, ST JOHN'S CHURCH, SIDCUP, SATURDAY 21 MAY 2022, 7.30PM

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957), Karelia Suite, Op.11

I. Allegro moderato

II. Adagio di molto

III. Allegro, ma non tanto

In 1893 the Vyborg Students’ Association commissioned Sibelius to compose incidental music for scenes from Karelia’s history. This region is the frontier land of Eastern Finland bordering Russia, into which much of it, including the city of Vyborg, was annexed by the USSR in 1945 and remains under Russian occupation. The stage work planned by the Students’ Association was an exercise in Finnish cultural assertion, described neutrally as a ‘lottery to promote the education of the people of Vyborg Province’ to avoid Tsarist censorship. However the titles of the scenes were more explicit, including ‘A Karelian Home: A Message about War (the year 1293)’,’The Siege of Vyborg (1770)’ and ‘Karelia is reincorporated into the Grand Duchy of Finland (1811)’.

The commission gave Sibelius a reason to resume his study of Karelian rune singing and Swedish medieval ballads, and more prosaically, the 500 Mark fee paid the composer’s rent for six months. The full incidental music, which included both the Karelia Suite and Overture op.10, was first performed on 13 November 1893, conducted by Sibelius. Ernest Lampén, a spectator, recalled the reception:

‘The noise in the hall was like an ocean in a storm. I was at the opposite end of the hall and could not distinguish a single note. The audience did not have the patience to listen and was hardly aware of the music. The orchestra was actually there, behind the pillars. I thrust my way through the crowd and managed to reach the orchestra after a good deal of effort. There were a few listeners: just a handful. I arrived just when they were playing the march. What an extraordinarily charming and varied melody! What a springy rhythm! ... I hadn't heard such attractive music from Sibelius before.’

Fortunately for Sibelius, his Karelia music was performed at a concert a week later in more dignified surroundings: this critical praise he received helped to launch his career as Finland’s leading composer, as well as a symbol of national identity. Sibelius turned three movements into a Concert Suite, also publishing the Overture separately. In the first movement, Intermezzo, the orchestra divides starkly in function: strings provide atmosphere and rhythm throughout, while horns, then full winds, brass percussion depicts a procession of tax collectors. The Ballade evokes medieval Swedish King Karl Knutsson, reminiscing in his castle while a minstrel plays for him (the cor anglais solo). The finale, Alla Marcia, originally was incidental music for a castle siege tableau.

I. Allegro moderato

II. Adagio di molto

III. Allegro, ma non tanto

In 1893 the Vyborg Students’ Association commissioned Sibelius to compose incidental music for scenes from Karelia’s history. This region is the frontier land of Eastern Finland bordering Russia, into which much of it, including the city of Vyborg, was annexed by the USSR in 1945 and remains under Russian occupation. The stage work planned by the Students’ Association was an exercise in Finnish cultural assertion, described neutrally as a ‘lottery to promote the education of the people of Vyborg Province’ to avoid Tsarist censorship. However the titles of the scenes were more explicit, including ‘A Karelian Home: A Message about War (the year 1293)’,’The Siege of Vyborg (1770)’ and ‘Karelia is reincorporated into the Grand Duchy of Finland (1811)’.

The commission gave Sibelius a reason to resume his study of Karelian rune singing and Swedish medieval ballads, and more prosaically, the 500 Mark fee paid the composer’s rent for six months. The full incidental music, which included both the Karelia Suite and Overture op.10, was first performed on 13 November 1893, conducted by Sibelius. Ernest Lampén, a spectator, recalled the reception:

‘The noise in the hall was like an ocean in a storm. I was at the opposite end of the hall and could not distinguish a single note. The audience did not have the patience to listen and was hardly aware of the music. The orchestra was actually there, behind the pillars. I thrust my way through the crowd and managed to reach the orchestra after a good deal of effort. There were a few listeners: just a handful. I arrived just when they were playing the march. What an extraordinarily charming and varied melody! What a springy rhythm! ... I hadn't heard such attractive music from Sibelius before.’

Fortunately for Sibelius, his Karelia music was performed at a concert a week later in more dignified surroundings: this critical praise he received helped to launch his career as Finland’s leading composer, as well as a symbol of national identity. Sibelius turned three movements into a Concert Suite, also publishing the Overture separately. In the first movement, Intermezzo, the orchestra divides starkly in function: strings provide atmosphere and rhythm throughout, while horns, then full winds, brass percussion depicts a procession of tax collectors. The Ballade evokes medieval Swedish King Karl Knutsson, reminiscing in his castle while a minstrel plays for him (the cor anglais solo). The finale, Alla Marcia, originally was incidental music for a castle siege tableau.

Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840-93), Violin Concerto in D, Op. 35

I. Allegro moderato

II. Canzonetta: Andante – III. Finale: Allegro vivacissimo

Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto was composed in the Swiss resport of Clarens, on the shores of Lake Geneva, in 1878. Tchaikovsky was recovering from a bout of depression, following his failed marriage to Antonina Miliukova. Joined by his composition pupil, the violinist Iosif Kotek, he was inspired to compose his Violin Concerto, a work that, typically for Tchaikovsky, gives no clue to his immediate emotional circumstances. After several stalled attempts at scheduling performances, with violinists including the great Leopold Auer declining to play it, the première was given by Adolph Brodsky in 1881 in Vienna, conducted by Hans Richter. Initial critical reception generally was unfavourable: Edouard Hanslick wrote that ‘the violin was not played but beaten black and blue’. Within a few years, however, the work establish itself as one of the greatest virtuoso concertos in the repertoire, and was adopted by violinists including Leopold Auer who had initially rejected it.

I. Allegro moderato

II. Canzonetta: Andante – III. Finale: Allegro vivacissimo

Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto was composed in the Swiss resport of Clarens, on the shores of Lake Geneva, in 1878. Tchaikovsky was recovering from a bout of depression, following his failed marriage to Antonina Miliukova. Joined by his composition pupil, the violinist Iosif Kotek, he was inspired to compose his Violin Concerto, a work that, typically for Tchaikovsky, gives no clue to his immediate emotional circumstances. After several stalled attempts at scheduling performances, with violinists including the great Leopold Auer declining to play it, the première was given by Adolph Brodsky in 1881 in Vienna, conducted by Hans Richter. Initial critical reception generally was unfavourable: Edouard Hanslick wrote that ‘the violin was not played but beaten black and blue’. Within a few years, however, the work establish itself as one of the greatest virtuoso concertos in the repertoire, and was adopted by violinists including Leopold Auer who had initially rejected it.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975), Symphony No. 9

I. Allegro

II. Moderato

III. Presto – IV. Largo – V. Allegretto - Allegro

During World War Two, Shostakovich wrote three symphonies: Numbers 7, 8 and 9. The first, the Leningrad, is a vast, overtly patriotic work – a 20th-Century 1812 Overture writ large, complete with a musical battle; it caught the public imagination in the Soviet Union and Western nations with frequent performances and broadcast. The Eight is longer still, offering a deeper essay in anguish and tragedy. Shostakovich said in 1943 that his Ninth would be a monumental work for orchestra, soloists and chorus ‘about the greatness of the Russian people, about our Red Army liberating our native land from the enemy’, and in 1944, ‘a large-scale work in which the overpowering feelings ruling us today would find expression. I think the epigraph to all our work in the coming years will be a single word – “Victory”.’ The example of Beethoven’s huge Ninth Symphony only heightened expectations.

The reality was different. Shostakovich completed his Ninth in summer 1945, just after the ‘Great Patriotic War’ ended. Instead of a victory celebration, he wrote a compact work for chamber orchestra, as individual a response to conflict as Vaughan Williams’ Fifth Symphony – a heartfelt cry for peace amid war. According to the controversial memoirs Testimony, related by Solomon Volkov, Shostakovich said:

'They wanted me to write a majestic Ninth Symphony. ... When the war against Hitler was won ... everyone praised Stalin, and I was supposed to join in this unholy affair. ... I confess that I gave hope to the leader and teacher’s dreams. I announced I was writing an apotheosis. I was trying to get them off my back, but failed. When my Ninth was performed, Stalin was incensed. He was deeply offended because there was no chorus, no soloists. And no apotheosis. There wasn’t even a paltry dedication. It was just music, which Stalin didn’t understand very well and which was of dubious content. I couldn’t write an apotheosis to Stalin. I simply couldn’t.'

The Ninth is superficially joyful, even manic, but suffused with satire and pathos. The first movement opens in apparent high spirits, but frequently hints at darkness and insecurity – including destabilising its basic 2/4 meter. It ends without ceremony and only the most cursory closure. The second movement is muted and morose, scored barely, with moments of grotesque. The third movement is a fast dance, turning into savage fair-ground music with ricochet string writing and biting trumpet solo. It burns out, and is interrupted by trombones and tuba – the fourth movement. Gaiety is over; a piercing trumpet entrance heralds an elegiac bassoon solo. From this, the fifth movement emerges. Its mood is difficult to define: is Shostakovich joking, celebrating, satirising, or a combination of all of these and more? The movement turns into a savage parade, with disruptive moments and surprises worthy of Haydn.

The first performance was in St Petersburg (then Leningrad) in November 1945, conducted by Yevgeny Mravinsky, and broadcast live, sharing the programme with Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony – an unlikely companion work. Musical colleagues and audience responded favourably; fellow composer Gavriil Popov described it as:

'Transparent. Much light and air. Marvellous tutti, fine themes (the main theme of the first movement – Mozart!). Almost literally Mozart. But, of course, everything is very individual, Shostakovichian ... a marvellous symphony. The finale is splendid in its joie de vivre, gaiety, brilliance, and pungency!'

Soviet officialdom would soon turn against Shostakovich. Stalin and the ruling Bolshevik elite were furious with this tongue-in-cheek Ninth, confounding their expectations. Critics started denouncing its ‘ideological weakness’ and failure to ‘reflect the true spirit of the Soviet people’; in 1948 Shostakovich’s music was denounced in the Zhdanov Decree and his Ninth Symphony banned in the Soviet Union. Shostakovich lived in fear of arrest until Stalin’s death in 1953; he composed mainly film music in public and chamber music in private. Only in 1955 was the Ninth performed again.

I. Allegro

II. Moderato

III. Presto – IV. Largo – V. Allegretto - Allegro

During World War Two, Shostakovich wrote three symphonies: Numbers 7, 8 and 9. The first, the Leningrad, is a vast, overtly patriotic work – a 20th-Century 1812 Overture writ large, complete with a musical battle; it caught the public imagination in the Soviet Union and Western nations with frequent performances and broadcast. The Eight is longer still, offering a deeper essay in anguish and tragedy. Shostakovich said in 1943 that his Ninth would be a monumental work for orchestra, soloists and chorus ‘about the greatness of the Russian people, about our Red Army liberating our native land from the enemy’, and in 1944, ‘a large-scale work in which the overpowering feelings ruling us today would find expression. I think the epigraph to all our work in the coming years will be a single word – “Victory”.’ The example of Beethoven’s huge Ninth Symphony only heightened expectations.

The reality was different. Shostakovich completed his Ninth in summer 1945, just after the ‘Great Patriotic War’ ended. Instead of a victory celebration, he wrote a compact work for chamber orchestra, as individual a response to conflict as Vaughan Williams’ Fifth Symphony – a heartfelt cry for peace amid war. According to the controversial memoirs Testimony, related by Solomon Volkov, Shostakovich said:

'They wanted me to write a majestic Ninth Symphony. ... When the war against Hitler was won ... everyone praised Stalin, and I was supposed to join in this unholy affair. ... I confess that I gave hope to the leader and teacher’s dreams. I announced I was writing an apotheosis. I was trying to get them off my back, but failed. When my Ninth was performed, Stalin was incensed. He was deeply offended because there was no chorus, no soloists. And no apotheosis. There wasn’t even a paltry dedication. It was just music, which Stalin didn’t understand very well and which was of dubious content. I couldn’t write an apotheosis to Stalin. I simply couldn’t.'

The Ninth is superficially joyful, even manic, but suffused with satire and pathos. The first movement opens in apparent high spirits, but frequently hints at darkness and insecurity – including destabilising its basic 2/4 meter. It ends without ceremony and only the most cursory closure. The second movement is muted and morose, scored barely, with moments of grotesque. The third movement is a fast dance, turning into savage fair-ground music with ricochet string writing and biting trumpet solo. It burns out, and is interrupted by trombones and tuba – the fourth movement. Gaiety is over; a piercing trumpet entrance heralds an elegiac bassoon solo. From this, the fifth movement emerges. Its mood is difficult to define: is Shostakovich joking, celebrating, satirising, or a combination of all of these and more? The movement turns into a savage parade, with disruptive moments and surprises worthy of Haydn.

The first performance was in St Petersburg (then Leningrad) in November 1945, conducted by Yevgeny Mravinsky, and broadcast live, sharing the programme with Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony – an unlikely companion work. Musical colleagues and audience responded favourably; fellow composer Gavriil Popov described it as:

'Transparent. Much light and air. Marvellous tutti, fine themes (the main theme of the first movement – Mozart!). Almost literally Mozart. But, of course, everything is very individual, Shostakovichian ... a marvellous symphony. The finale is splendid in its joie de vivre, gaiety, brilliance, and pungency!'

Soviet officialdom would soon turn against Shostakovich. Stalin and the ruling Bolshevik elite were furious with this tongue-in-cheek Ninth, confounding their expectations. Critics started denouncing its ‘ideological weakness’ and failure to ‘reflect the true spirit of the Soviet people’; in 1948 Shostakovich’s music was denounced in the Zhdanov Decree and his Ninth Symphony banned in the Soviet Union. Shostakovich lived in fear of arrest until Stalin’s death in 1953; he composed mainly film music in public and chamber music in private. Only in 1955 was the Ninth performed again.